Tuesday, July 20

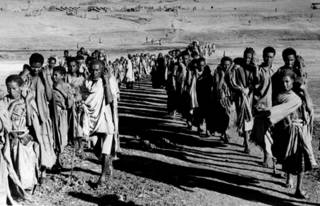

let the ferenjis feed 'em

Refugees at home. Source. food security is for foreigners to worry about, bad policies are for foreigners to fix

Professor Jeffrey Sachs, the special adviser to UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan on the Millennium Development Goals stated of Ethiopia that

"This is a country living right on the edge"He also was critical of the West noting that the

"they are providing 100 times more for the emergency than for prevention," he said. "If all you give is food aid, you will be giving it forever." He warned that "terrible things" could happen both in Ethiopia and the region if the poverty crisis were not tackled.Criticism of the West is appropriate but not for the reason stated by Sachs.

The West has allowed the government to totally abdicate responsibility for its own people. The West, particularly the U.S., and international agencies willingly provide food aid but leave alone a government that does not ensure pro-agricultural policies are implemented to begin with.

For example, in Ethiopia there is no right to private ownership of land.

Ethiopia's own government values political control and guarantees of its own survival over liberalization of the economy and the people from intrusive state controls.

So when foreign pressure is tried how does the Ethiopian Government respond? Take a look at the The San Francisco Chronicle - Ethiopia's empty promise: Rushed resettlement leads to hunger and death it details another tragic chapter in this story.

Under pressure from international donors tired of giving millions of dollars in food aid to help Ethiopians at risk of starvation, the Ethiopian government came up with a quick fix -- move them.The West is like a third party enabler in an abusive relationship. The essential message is "do what ever you want, just give me a chance to feed your people". Well, someone has to see that the people are fed and it sure ain't the Ethiopian government.

Two million of them.

The government of Prime Minister Meles Zenawi insisted the program is voluntary and said settlers are given land, food, safe water, grain mills, health care, schools and roads as incentives to relocate.

Last year, 20 years after a million Ethiopians died in a famine that caught the attention of the world, the U.N. World Food Program declared 13 million Ethiopians in danger of starvation. This year, the rains have been a little better, but 7 million are still near starvation.

The government asserted in January that resettled farmers achieved food self-sufficiency in the first year of the program, producing a surplus in the first harvest. But the World Bank, the U.N. mission in the country and other organizations, including Doctors Without Borders, have criticized the government's management of the resettlement program, saying that rather than combat famine, the hasty exodus has led to a humanitarian crisis in many areas.

There is a well-established international aid system in this nation of 70 million, but Desalegn Rahmato, director of the Ethiopian Forum for Social Studies, said, "The government is reluctant to ask for food aid, because this would prove the failure of the resettlement program."

Genocide Watchwas deeply worried about the disastrous resettlement story back in March: "Ethiopia to shift a million people from drought-hit areas" .

Ethiopia has begun a resettlement programme which aims to move up to a million people away from the country's drought-stricken and over-worked central highlands to more fertile regions.

Tens of thousands of families are to be moved before the rains come in May as the result of a pilot project last year, which the government says resulted in improved harvests.

Critics say the lands available for resettlement - mainly along Ethiopia's border with Sudan - are in areas notorious for diseases including malaria and kala azar or visceral leishmaniasis, a potentially fatal disease transmitted by sandflies.

Attempts to resettle farmers are not new in Ethiopia but this is the biggest relocation scheme in the country's history.